https://joelssermons.files.wordpress.com/2020/03/20200301sermon.mp3

Texts: 1 Corinthians 1:18-20; 2:1-5

Speaker: Joel Miller

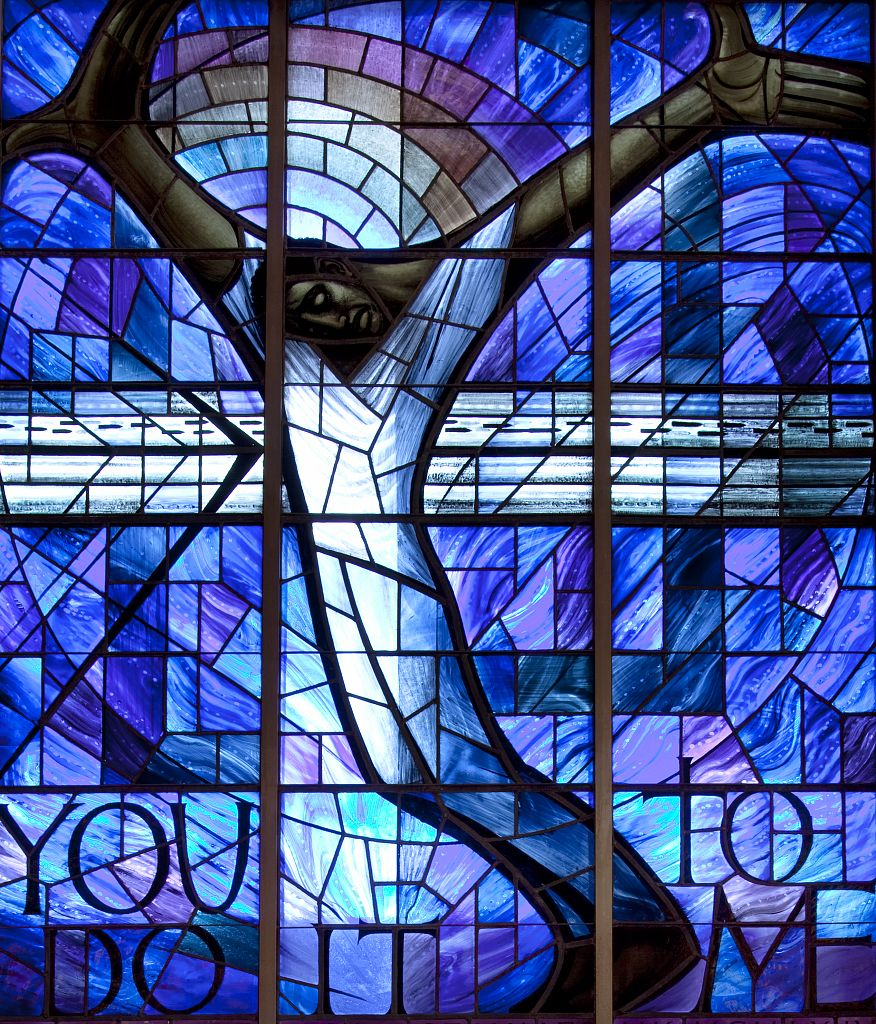

The image behind me and on your bulletins is a stained glass window in the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. That’s the church that was bombed in 1963. It was a Sunday morning in September, and there were about 200 people in the building when the bomb exploded. Four black girls were killed. Addie Mae Collins, age 14. Cynthia Wesley, age 14. Carole Robertson, age 14. Denise McNair, age 11.

The stained glass window was a gift from a Welsh artist. He was so moved by the tragedy that he raised money throughout Wales – especially inviting children to donate – in order to create this window as a permanent installation in the church. It was one of the first public depictions of a black Christ in the deep South.

One of its messages is told in the positioning of the hands. The left hand is held open, a sign of openness, of welcome, of surrender to the will of God. The right hand is held up as if holding off the very forces of evil themselves. A sign of resistance and refusal to have one’s humanity diminished by the hatred and violence directed against it.

Another message is in the writing at the bottom – five words, drawn from Matthew chapter 25. “You do it to me.” That’s the passage where Jesus tells the parable in which both the sheep and the goats learn that whatever they did to “the least of these” they have done it to Christ. Feeding the hungry, welcoming the stranger, clothing the naked, visiting the sick and imprisoned. Whatever you have – or haven’t done – to these “You do it to me.”

To have those words beneath a crucified Christ in a church where four girls were murdered is an invitation to use one’s theological imagination and directly identify those girls in the place of Christ and Christ in the place of those girls. Everyone who has seen and will see this stained glass window is confronted with the message that the bombers, in their zeal that they likely related to some form of Christian faith, deranged as it was, were actually re-crucifying Christ. “You do it to me.”

The cross is a brutally violent image. In first century Rome it was an instrument of torture and death, reserved especially for slaves, and those of the lower classes deemed enemies of the state. It was extreme in its horror, designed to be a public display of absolute power for those doing the crucifying, public humiliation for the one crucified, and fear for those viewing it all. Crosses were displayed in prominent places. On hills, at crossroads. Like a billboard. An advertisement for the justice of the state, the peace of Rome.

Which makes it all the more remarkable that the cross became such an important symbol for a little Jewish sect whose leader had been crucified. The gospels give a disproportional amount of attention to that final week of Jesus’ life. According to my math, which you’re free to double check, there are 89 total chapters in the four gospels, 27 of which cover Palm Sunday and after. That’s a shave over 30% of gospel material where the cross looms large, either as an impending event, or in the immediate aftershocks. This doesn’t count the times before this when Jesus starts to prepare his followers for this possibility.

Still, Anabaptists have played an important role in reclaiming the other 70% of the gospels – the life and teachings that got Jesus in trouble in the first place.

The Apostle Paul never met the flesh and blood person of Jesus. He adopted the message of death and resurrection as a central part of the gospel he preached. He wrote to the Corinthians, “For I decided to know nothing among you except Jesus Christ and him crucified.” If you read the rest of the letter you realize that’s a bit of an overstatement, but it does hold that the head-spinning reality of Christ crucified was the basis of Paul’s teachings. In his own words, it was foolishness to the wise, but it was God’s foolishness. By willingly undergoing death, Jesus defeated death. By not responding to violence in kind, Jesus made peace. By lowering himself, Jesus flipped the cosmic hierarchy and became exalted. In being raised to new life, Jesus raised all with him. These themes run throughout Paul’s letters to those early churches.

That little Jewish sect grew large and powerful enough that eventually Rome became Christianized. Although one could argue just as well that Christianity became Romanized. For all his faults, the emperor Constantine, after his conversion, was the one to end the practice of Roman crucifixion, in the year 337.

By that time the cross meant more than just an instrument of capital punishment. It was and is an object of theological reflection about the character of God and humanity and, no small matter, salvation.

The legacy of the cross now includes crusades and inquisitions and slave owners. And slaves who found in the religion of their masters a figure with whom they deeply identified.

The cross has meant many things.

The cross is a symbol of the empire that crucified Jesus. It is a symbol of the Christ who presented an alternative kingdom and undermined the power of empire from within its own game. It is a symbol of a Christianized empire that took the cross out into battle to conquer the heathens and Muslims.

The cross is something to hang in your hallway at home, or around your neck. To etch in your pulpit. The cross is a sign that God loves you. It means that evil has been conquered and the war is over, we just haven’t realized it yet. The cross means no more crosses.

The cross means God bless America. It means that God, in order to forgive sin and save us from the wrath of hell, had to send his son as a perfect sacrifice. It means Jesus is the only way to the Father.

The cross means if you want to truly live, you first must let go of everything. It means death never has the last word. It means when God visited humanity, we killed her.

Back at the beginning, the meaning of the cross was reversed, then reversed back, then reversed again how many times over?

The writer John Tucker (1) talks about how we might understand a religious way of seeing in the post-Enlightenment world by giving an overview of the history of glass – stained and clear. While no one’s quite sure when glass was invented, the earliest examples we have are colored, used with pottery and jewelry. It was decorative and ornamental. He writes, “In those days, glass was looked at, not through.” (P. 4)

The Romans make an appearance in this story too. They were the first to find a technique for making clear glass. From that point forward, clear glass and colored glass coexisted. Glass historians say that between the years 1100 and 1700 glass started being used for windows. Stained glass windows started showing up in churches. Clear glass windows started showing up in homes.

Tucker suggests that the development of these two uses of glass illustrate two distinct different ways of seeing that came with the Enlightenment – often in conflict, not necessarily so – over the purpose of light and the nature of enlightenment.

One way of seeing the world is through clear glass. These windows in our homes allow the out of doors to be seen without us having to go outdoors. The light comes right through and we perceive the object directly. This is how the scientific mind works. In fact, a significant part of the scientific endeavor is to clear as much dust off the glass as possible in order to see what’s on the other side of the glass as accurately as possible. This made me think of that high powered telescope in the observatory in the desert of Chile. It’s one of the best places on earth to view the stars because there’s hardly any humidity in the air and no light pollution. In other words, the glass is clearer there than just about anywhere on earth, better enabling the scientific advance of knowledge of the stars.

Scientific experiments get criticized when peers are able to point out a fog on the proverbial glass interfering with what is being observed. This way of seeing, which we fully affirm, has brought us tremendous knowledge and a certain form of enlightenment.

Tucker doesn’t consider himself a believer, so he’s not trying to justify the existence of religion, but he does grant religion the realm of the stained glass window. He gives credit to the Benedictines as being responsible for the idea that the light shining through stained glass is a way of expressing and experiencing the glory of God. He writes this:

The (stained glass) windows were not only something to be looked at and appreciated, they also bathed the room and those in it in a different kind of light than was normally experienced in daylight. Anyone who has been in a room that is illuminated by stained-glass windows has experienced what makes that light different from the light that comes through a transparent window. The words that come to mind are religious words like holy or sacred or reverential. In other words, stained glass differs from transparent glass in that it is looked at rather than through, and the altered light that bathes the room changes the way you see yourself and others.” (P. 5)

I find this fairly compelling. Especially with the image and story of this particular stained glass window in front of us. It makes me wonder if the cross itself serves as a kind of stain glass window. What if the cross offers itself to us as a particular way of filtering the light of human experience? What if the cross, like a stained glass window, alters the light that bathes the room of our lives, changing the way we see ourselves and others? Hold up the cross to history, or the daily news, or your own life, and you get a particular set of colors that don’t show up if you were looking through clear glass. Like the message of this window at 16th Street Baptist Church. The artist would have you see that what was attacked in that bombing was not only four black girls, but the very personhood and sacredness of Christ. Can you see it? Can you perceive that gift of Enlightenment?

I wonder if a similar insight is what ignited the soul of the Apostle Paul who started to see everything on every level of existence through the prism of the dying and rising Christ. All the way down into the inner most recesses of the soul, like the dying of the ego driven self and the rising of the Christ-in-me, symbolized in baptism. Into interpersonal relationships where we see in the suffering of others a reflection of God’s suffering in this world. All the way up to the political and the cosmic where the death dealing powers that seek to preserve their own lives get continually exposed and ultimately defeated through the nonviolent triumph of Christ.

This Lent we’ll be looking at and through the stained glass window of the cross. It has meant many things in many times. You are invited, this season, to consider anew what it means for us.

(1) John Tucker, Zero Theology: Escaping Belief through Catch-22s, Cascade, 2019.