CMC Sunday Meditations | 22 March 2020 | Lent 4

The Cross and Atonement

As we meet today in spirit but not in person, we gather around these Sunday Meditations offered by members of the CMC community. Just as we light the Peace Candle to begin our worship, you are invited to light a candle for these Meditations. The flame joins us in spirit across distance, along with our sister church in Armenia, Colombia.

Opening Thoughts | Joel Call

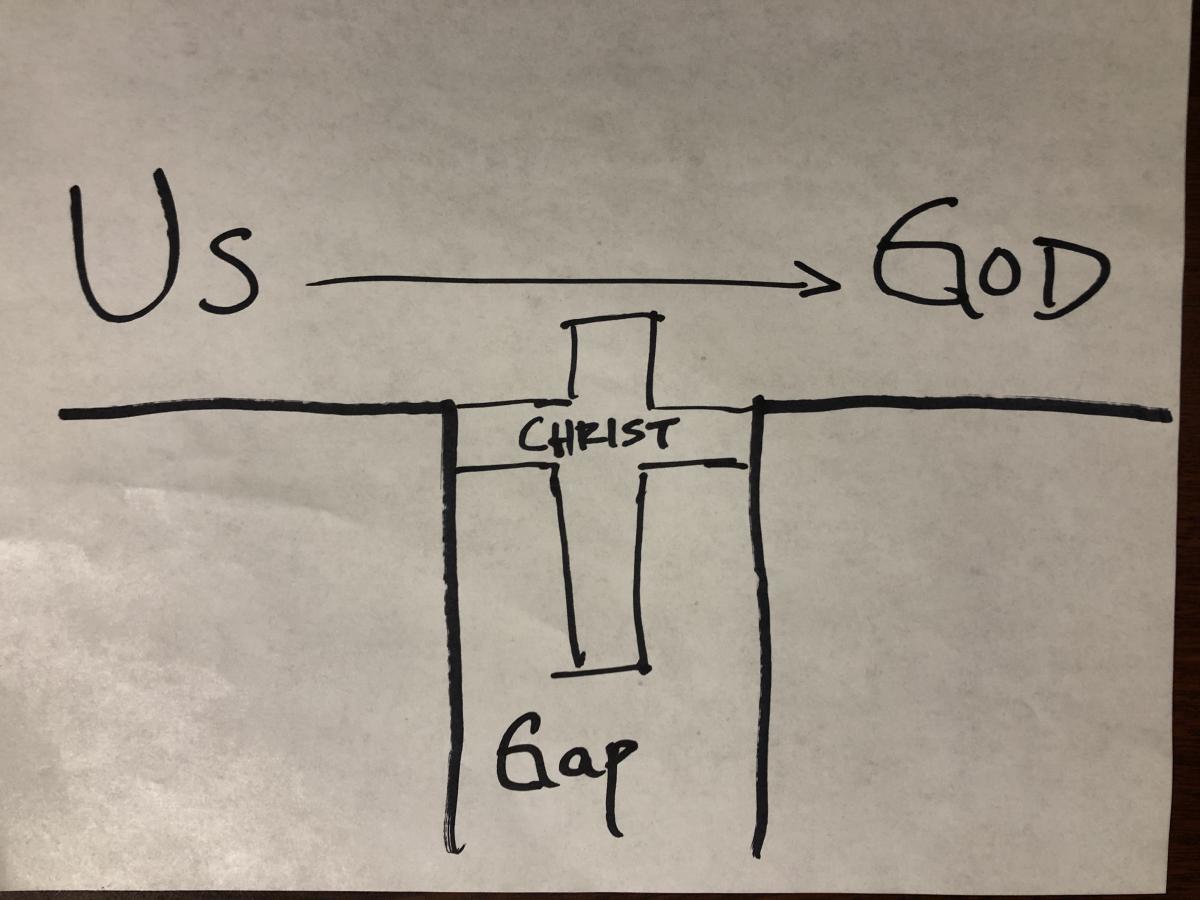

I grew up with the picture above. The crude sketch is a basic illustration of the underlying logic of how I was taught to understand Christ’s death on the cross, and how it saves me, i.e., it was my atonement theology for most of my life. “We are separated from God.” The commentary on the drawing would always begin on this fundamental premise. There’s a gap between us and God, and Christ’s sacrifice effectively bridges this primordial gap, making a way for us to commune with the Divine; to be reconciled to God.

Today finds us separated from each other in new, unprecedented ways. In the realities of social distancing and self-quarantining, we find ourselves physically separated from each other. As we continue to figure out what community care looks like in this time, I invite us to question the authority of the “gap,” of the separation pictured in the drawing. What if communion–what if presence–with God, with neighbor, with self, isn’t a distant reality only a cross can bridge? What if being “saved” doesn’t require a bloody execution, but exists as a reality as close as your breath? In a call to your loved ones, a letter of love from a friend, in the gift of groceries?

Song and Children’s Time Video

Song: Let the Mystery Be by Iris DeMent | Jenny Campagna

Children’s Time | Elisa Leahy

CT 32220 from Gwen Reiser on Vimeo.

Mission Moment | Ruth Leonard Mennonite Partners in China

In early January we began to hear about the virus in Wuhan, China. We have been through this city by train— a huge city that nobody in America had heard of, a place with millions of people. The photos of it shutting down were astonishing- and then we worried about the spread of the disease northward to Henan Province.

I called our friend Zhao Feng- and indeed everything was closing in our old densely-packed city as well. It sounded dire- and we spent the next two months concerned about his family. They were in lockdown. But two weeks ago Feng contacted us by WeChat and again on Sunday. He was seeing our problems on the news, and watched our governor give an update about Ohio. His family, now beginning to return to a new normal, was worried about ours!

Our friend Jiang Jiang has also been in communication. She has been in her village since the lockdown before Spring Festival. Nobody can go in or leave the village.

This all sounded strange- until this week.

This is what serving with Mennonite Partners in China did for us. We left to teach , make friends, and be bridge-builders we were told. The bridge was built —and it went both ways. We are forever connected to these kind people who care about us, and you.

Since 1981, 300 Mennonites from the US and Canada have served in China as teachers. The current teachers are still in uncertain times as the universities have not reopened. Many were stranded out of the country on holiday when the virus struck.

In the midst of this all, I will leave you with something weirdly funny Feng told us. He said, ”This disease came from bats. It’s ridiculous to eat bats. The bats, for thousands of years have been trying to evolve into something so ugly no one would eat them! So, it is their revenge- if people are ridiculous enough to eat them, they will get bad germs!” It made me laugh. And I need to laugh.

Stay safe everyone.

The photo below was taken last week. It shows Feng with his daughter Amy and his Mother. Our Chinese family.

Ruth, Rick, Neil, and Thomas Leonard left for China in 2003, just after the SARS epidemic, to serve through MCC with MPC. They lived in Henan for three years. Later, Ruth continued on teaching five more years, and brought 4 summer tours of Chinese students to America. Many in the church have been involved with these groups.For more photos from China, go to the Mennonite Central Committee website: MCC celebrates its100th birthday in 2020! 100 stories. Rice lessons

Song | Room on the Cross by Scott Miller (found at 12m47sec on link) | Brent Miller

Sermon | Joel Miller

The Cross and Atonement

Colossians 2:15 (Christ) disarmed the rulers and authorities and made a public spectacle of them, triumphing over them (on the cross).

Hebrews 2:14-15 Since, therefore, the children share flesh and blood, he himself likewise shared the same things, so that through death he might destroy the one who has the power of death, that is, the devil, 15 and free those who all their lives were held in slavery by the fear of death.

Truth be told, I almost didn’t include Atonement as one of the themes for Lent. Here’s one of the reasons why:

The writer John Tucker, whose metaphor we’ve already borrowed, likening the religious way of seeing to a stained glass window, writes: “Theological explanation is theology at its worst.” (1)

I tend to agree.

Rather than theology as explanation, I much prefer theology as parable, poetry, paradox, prayer and story. Theology as a question that won’t let go.

Which puts us in a bit of a bind with the theme The Cross and Atonement. Because the relationship between atonement – the reconciliation of God and humanity – and the cross is frequently a formula-like package of dense theological explanation.

Perhaps there’s an explanation for that.

For the last few weeks we’ve been talking of Jesus’ crucifixion as one of many. Hundreds. Hundreds of thousands. Crucifixions were a common sight within Roman-occupied territory and, for those with eyes to see, a common sight throughout history – including racial terror lynchings and the persecution of LGBTQ persons in the US.

The crucifixion of Jesus was one of many.

And yet….YET, it remains utterly unique.

While countless others have also been put to death by mob violence and/or the will of the state, only the death of Jesus on a cross has been elevated as having something to do with dying for the sins of the world. Something to do with righting the relationship between humanity and our Creator. Something about defeating the Satan and all the principalities and powers that set themselves against the peaceable kingdom of God. Something to do with the salvation of humankind — and not just our late-on-the-scene species, but, in the words of the Apostle Paul, through Christ “…the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God.” (Romans 8:20)

Wow. How does all that work?

Maybe that does need some explanation.

Here’s a really bad one:

God is so righteous nothing impure can enter God’s presence. God is so just that God demands punishment for sins to balance the score. All humans are sinful and therefore deserving of eternal separation from God, hell. But God is also loving and sent his Son Jesus to die in our place, a perfect sacrifice, thus satisfying the wrath of God for all time. By believing all this to be true, God is able to forgive your sins, and you are saved.

Congratulations.

Now go tell others before it’s too late for them.

This is another reason why we almost skipped the Atonement theme.

This only-slightly-caricatured explanation, or theory, of atonement, dominant throughout American conservative evangelicalism, is so problematic one is strongly tempted to just change the subject. What’s even more problematic is that many progressive people of faith also accept this as the explanation of atonement, such that when they realize they can’t believe in a God who needs to kill someone in order for things to be all good they start questioning whether they can still be Christians.

If you’re searching for a substantive, biblically grounded take-down of bad atonement theology, wrapped up in a much more life giving and, according to the gay Catholic priest who writes it, a much more conservative telling of atonement, I recommend this essay:

“Some Thoughts on Atonement,” by James Alison.

It is rather dense, but if you stick with it, the rewards are in the second half. It’s the closest thing you’ll get today to a good explanation on what the New Testament writers understood Jesus to be doing regarding atonement.

For a slightly different approach, I invite you to consider with me this image, which appeared as public art on a London bridge (initially falsely contributed to the artist Banksy).

What’s immediately striking about this image is that this is our world. Atonement is nothing if it isn’t about our world. The real one of police and press, body and blood.

This re-imagining of the setting through which Jesus carries his cross invites further imagining. Let us imagine that the officers and the media are merely the inner circle of a scene that includes many other characters past and present.

There is Judas, disillusioned with whatever he thought Jesus would become, selling his insider knowledge to the religious authorities who wish Jesus dead.

And there is Mary Magdelene who remains near Jesus to the end – the first to announce resurrection.

There are the religious and political authorities who cling to order and power over mercy and justice.

And there is a cohort of wounded healers who no longer seek the approval of the institution to live within their truth.

There are protestors and counter-protestors.

There are evangelicals who believe Jesus goes to his death in their place to save them from their personal sins.

There are liberals who believe Jesus is doing battle with the demonic forces of empire that Rome now represents.

There are Buddhists and Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs who look on through the eyes of their own tradition.

There are historians probing for facts on the ground, searching for a narrative arc.

There are poets pronouncing beauty and horror.

There are children asking questions and adults left mumbling answers they aren’t sure they believe.

There are birds overhead.

There are stones underfoot that were formed before there were birds, long before people.

There are plants pushing up between these stones, catching sunlight.

Not all these characters can be painted on a bridge in London, but let’s imagine them as a part of a grand extended scene.

This is the world in all its glory and brokenness. This is creation on the verge of obtaining the freedom of the children of God.

And there is Jesus in the center of it all. He will not make it through the day alive.

Jesus will give his final parable, this time with body and blood.

This is a world that rejected, and rejects Jesus, but which Jesus did not, and does not reject. None of it. And not a single being within it. Jesus does not react to the officer raising the baton as if that is the defining act of the officer’s humanity. Jesus offers the bread and cup to Judas just the same as the others. Jesus looks up, sees the bird in flight, and knows holy spirit is near.

While the press is busy pressing, protestors protesting, betrayers betraying, believers believing, adults #adulting, Jesus is busy messing with all our ideas of ourselves and God. Jesus occupies the finite space of material existence in a way that exposes the narrowness of our thinking and doing. Makes a public spectacle of them, in the words of Colossians. All the while pushing wide the horizon of being. Opening it up toward a freedom so terrifying and glorious one cannot walk toward it and be left unchanged. Bearing our sorrows we didn’t even know we had until they were reflected back to us. Offering grace that costs us nothing and everything if we would but let it sink in, all the way in, and then further in still.

Could this be the salvation of the world?

How to explain that?

Are we atoned?

And if so, what then?

(1) John Tucker, Zero Theology: Escaping Belief Through Catch-22s, Cascade Books, p. 83