Scripture: 1 John 4:18-21; Luke 4:18-19

Speaker: Paisha Thomas

Good morning!

Thank you to Pastor Joel for your constant demonstration of what it means to be God’s church, and God’s will being done on earth as it is in heaven.

Thank you to Adam Glass for brokering the generous donation that your congregation made to our new non profit LotF. And to all of you for your contributions.

Paul and Jacqui for your preparation excellence this week

And my two friends who are here for moral support.

Let the words of my mouth and the meditations of our hearts be acceptable in your sight oh lord, our strength and our redeemer. Amen and Asé.

From the Revised Common Lectionary – NRSV

1 John 4:12-21

4:12 No one has ever seen God; if we love one another, God lives in us, and God’s love is perfected in us.

4:13 By this we know that we abide in God and God in us, because God has given us of God’s Spirit.

4:14 And we have seen and do testify that the Father has sent his Son as the Savior of the world.

4:15 God abides in those who confess that Jesus is the Son of God, and they abide in God.

4:16 So we have known and believe the love that God has for us. God is love, and those who abide in love abide in God, and God abides in them.

4:17 Love has been perfected among us in this: that we may have boldness on the day of judgment, because as God is, so are we in this world.

4:18 There is no fear in love, but perfect love casts out fear; for fear has to do with punishment, and whoever fears has not reached perfection in love.

4:19 We love because God first loved us.

4:20 Those who say, “I love God,” and hate their brothers or sisters, are liars; for those who do not love a brother or sister whom they have seen, cannot love God whom they have not seen.

4:21 The commandment we have from him is this: those who love God must love their brothers and sisters also.

God is Us – Sunday April 28, 2024. Columbus Mennonite Church

When we say that God is love or, God is light, or in today’s message, God is us. We may not necessarily mean that these nouns are being equated to God. Rather, these nouns or verbs are examples of the presence of God.

Considering the past, here in the present, and a hoped for future, we look to the stories today to see if we find such examples of love and even some hate to make sure we cover the shock value that is verse 20 of the text.

I will share more details from this first story for those who have not heard it yet.

My seventh great grandfather’s name is Johnson Crowder. He was one of approximately 390 people who had been enslaved on John Randolph of Roanoke’s plantation. Randolph had a complicated relationship with slavery. But he had written a will that would provide for the manumission of all of the enslaved people on his plantation. He would also purchase 3,200 acres of land for them in a free state – which turned out to be in Mercer County, Ohio. The execution of the will was delayed by Randolph’s family who were trying to have him declared “mad” to discredit the will, for madness was one of the ways in which a will could be nullified in those times. And after all, he couldn’t have been in his right mind to want to liberate all of those whom he and the generations before him had enslaved. A fun fact for our entertainment: Francis Scott Key was one of the executors of the will along with a judge named William Leigh. Both were Randolph’s friends. After thirteen years in litigation, the case was won and Johnson Crowder and the other some 390 people were free to go. The year was 1846. The date was May the 4th. This Saturday will mark 178 years since that day. They headed by wagon train – mostly on foot toward their promised land. They had walked from Virginia to Ohio and then boarded a ferry on the Ohio River toward their promised land. The Freed people arrived in Ohio, having faced all of the imagined dangers at that time in the south and in Ohio. But once they arrived they were met with more danger – not only resistance, but violence, including an armed militia who had also made their takeover into a political issue in Ohio which aligned with the anti-black legislation here at the time.

Is this God? Is this love?

Believe it or not, those who violently seized the land of my ancestors were people of faith who may have thought they loved God. Hear the words of their memorandum.

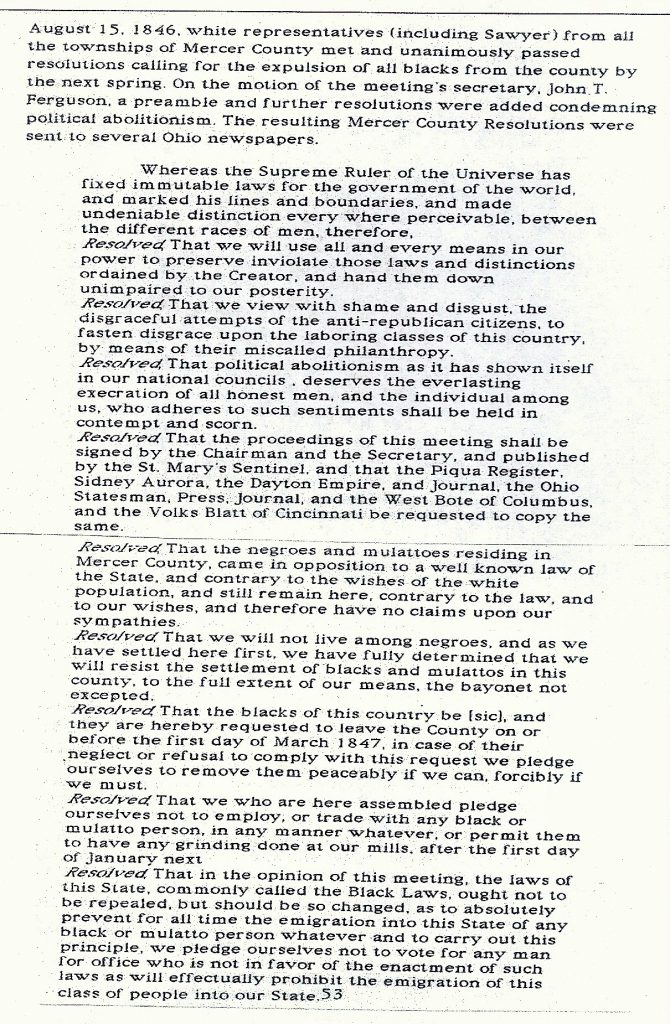

August 15, 1846 White representatives, [including Sawyer] from all the townships of Mercer County met and unanimously passed resolutions, calling for the expulsion of all blacks from the county by next spring. On the motion of the meeting’s secretary, John T. Ferguson, a preamble and further resolutions were added condemning political abolitionism. The resulting Mercer County Resolutions were sent to several Ohio newspapers.

Whereas the Supreme Ruler of the Universe has fixed immutable laws for the government of the world, and marked his lines and boundaries, and made undeniable distinction every where perceivable, between the different races of men, therefore,

Resolved, That we will use all and every means in our power to preserve inviolate those laws and distinctions ordained by the Creator and hand them down unimpaired to our posterity.

Resolved, That we view with shame and disgust, the disgraceful attempts of the anti-republican citizens, to fasten disgrace upon laboring classes of this country, by means of their miscalled philanthropy.

Resolved, That political abolitionism as it has shown itself in our national councils, deserves the everlasting execration of all honest men, and the individual among us, who adheres to such sentiments shall be held in contempt and scorn.

Resolved, That the proceedings of this meeting shall be signed by the Chairman and the Secretary, and published by the St. Mary’s Sentinel, and that the Piqua Register, Sidney Aurora, the Dayton Empire, and Journal, the Ohio Statesman, Press, Journal, and the West Bote of Columbus, and the Volks Blatt of Cincinnati be requested to copy the same.

Resolved, That the negroes and mulattoes residing in Mercer County, came in opposition to a well known law of the State, and contrary to the wishes of the white population, and still remain here, contrary to the law, and to our wishes, and therefore have no claims upon our sympathies.

Resolved, That we will not live among negroes, and as we have settled here first, we have fully determined that we will resist the settlement of blacks and mulattos in this county, to the full extent of our means, the bayonet not excepted.

Resolved, That the blacks of this country be [sic], and they are hereby requested to leave the county on or before the first day of March 1847, in case of their neglect or refusal to comply with this request we pledge ourselves to remove them peaceably if we can, forcibly if we must.

Resolved, That we who are here assembled pledge ourselves not to employ, or trade with any black or mulatto person, in any manner whatever, or permit them to have any grinding done at our mills, after the first day of January next.

Resolved, That in the opinion of this meeting, the laws of this State, commonly called the Black laws, ought not to be repealed, but should be so changed as to absolutely prevent for all time the emigration into this state of any black of mulatto person whatever and to carry out this principle, we pledge ourselves not to vote for any man for office who is not in favor of the enactment of such laws, as will effectively prohibit the emigration of this class of people into our state.

The State of Ohio essentially said, “ok”, thereby sanctioning this violence against my people.

Is this love? Is this God?

Eventually my ancestors, Crowder and his people, were allowed to settle in Rossville, a very small section of land just outside of Piqua – thanks to the social justice advocacy of the local Quakers who had helped persuade the people of Piqua to allow the Freed to settle there.

Of the Quakers’ advocacy,

Is this love? Is this God?

For those among us tempted to say, “That had nothing to do with me. I didn’t own slaves. I didn’t take anyone’s land.”

This article from the American Bar Association enlightens us to the impact of generational land loss.

“In a recent study, we used county-level Census of Agriculture data to estimate the value of the lost Black agricultural land from 1920 to 1997…results yield a cumulative value of Black land loss of about $326 billion.”

“This $326 billion is conservative in that it does not include data limitations, lost acreage prior to this study, and “other potential benefits to land ownership… such as the ability of landowners to have more control over their labor and free time, more access to capital to invest in other business ventures, and more resources to provide access to high-quality education for their children so the next generation could experience upward mobility.”

“This intergenerational aspect of land wealth is precisely what makes the estimation of historic Black land loss so relevant to discussions of racial wealth gaps today. As a result of having their land stolen from them, many Black landowners lost a valuable tool for wealth creation. Accordingly, while the children and grandchildren of white landowners reaped the benefits of ready access to capital—education, home ownership, and entrepreneurial safety nets—the children and grandchildren of dispossessed Black landowners faced the perils of migrating to inner-city ghettos—crime, poverty, and instability.”

“Thus, from one generation to the next, the initial racial wealth gap that opened through the legacy of slavery, Jim Crow, and land theft has grown wider and, without intervention, will continue to widen. To view racial wealth gaps as the result of individual differences in the propensity to save or in portfolio allocations [or pulling oneself up by one’s bootstraps] ignores this legacy of state-sanctioned discrimination that limited Black wealth building at the outset and persists today through intergenerational transmission of wealth and through ongoing discriminatory structures [such as redlining and gerrymandering] in our society.” (Dr. Dania V. Francis, 2023)

Is this love? Is this God?

1 John 4:12 No one has ever seen God; if we love one another, God lives in us, and God’s love is perfected in us.

1 John 3:17 asks this question: How does God’s love abide in anyone who has the world’s goods and sees a brother or sister in need and yet refuses help?- Mark Allan Powell, in his book Introducing the New Testament cites this as the only concrete example of showing love in community.

But we also find in the book of …

James 2:15-17 If a brother or sister is naked and lacks daily food – And one of you says to them, “Go in peace; keep warm and eat your fill,” [thoughts and prayers] and yet you do not supply their bodily needs, what is the good of that? – So faith by itself, if it has no works, is dead.

What does this all mean?

It means that if we love God, we must love God’s creations, God’s earth, God’s nature, and God’s humanity

It means that if God’s work is to be done, it will be done through us. No one is going to pop out of the sky and do the work that we are here to do, empowered by the Spirit of God in us. God is us.

If God’s love is to be shown, we can measure that love by our actions of love toward one another

What is being done? What does it look like to instantiate, or exemplify love in this situation of racial injustice and unjust racial wealth gaps?

Derek Burtch was born in Mercer County. His family owns Burtch Seed Company which has a market value today of $ 1,162,210.00 and occupies more than 90,000 square feet of land in Celina, Ohio in Mercer County. Since we met by chance just about one month ago, Derek has read the 522 page book called A Madman’s Will, written about John Randolph’s Freed People, and has persuaded his dad to read the book. They are currently searching the land records to see if their seed farm occupies any of the parcels purchased for my ancestors.

Julie Vore is a lawyer who also became a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution and works for JP Morgan Chase. Julie has been donating her time for land acquisition research. She has discovered all of the land titles for the 3,200 acres of land purchased for the Freed, continues to connect with college professors who are conducting mapping research as part of their curricula, and regularly donates to Land of the Freed through Chase’s donation matching program. She is also aggressively nudging me through the process to see if I have a patron ancestor who was in the American Revolution so that I can join DAR.

Hadley Drodge is a curator at the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center which is a Smithsonian installation at Ohio History Connection. In addition to curating, Hadley uplifts stories of Black history in Ohio and advocates for repair from state sanctioned violence against Black people through grant research and committee support for LotF.

I asked Derek what he would say to people who ask what they can do. He said, “Research your local and family history! If your family has been in America for a few generations, there’s bound to be something there.”

Do you know people in the field of law or any policymakers who might not fear using their power to challenge these Black Laws that still exist in hidden places?

As we find ourselves in God’s presence, and seek God’s guidance about how to show God’s love, I trust that God will show us the ways that we can demonstrate God’s love through action. God is us.

We are One in The Spirit,

We are One in The Lord.

We are One in The Spirit,

We are One in The Lord.

And we pray that all unity may one day be restored.

And they’ll know we are Christians by our love,

By our Love,

Yes they’ll know we are Christians by our love.

Let us pray:

Eternal Wisdom, we thank you for your presence now. Guide our hearts, our minds and our hands to show your love to all of the living on earth as it is in heaven.

Amen.

Bibliography

Dr. Dania V. Francis, D. G. (2023, January 6). American Bar Association . Retrieved from American Bar Association : by Dr. Dania V. Francis, Dr. Grieve Chelwa, Dr. Darrick Hamilton, Thomas W. Mitchell, Nathan A. Rosenberg, and Bryce Wilson Stucki